(“En el fondo lo único que ha dicho es que nadie sabe nade de nadie, y no es una novedad. Toda biografía da eso por supuesto y sigue adelante, que diablos. Vamos Johnny, vamos a casa que es tarde.” — Cortázar, El Perseguidor; lo mismo se puede decir de una autobiografía, o en este caso, un pequeño ensayo. Vamos, Johnny.)

In response to The New York Times article “650 Prompts for Narrative and Personal Writing.”

426. “How Much Does Your Life In School Intersect Life Outside School?”

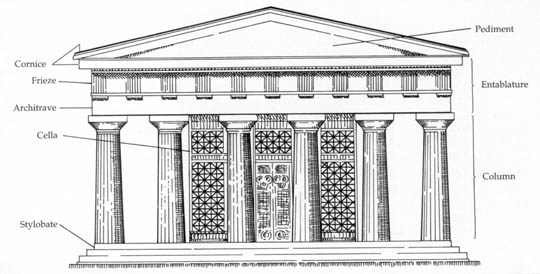

They meet like the columns of a Greek temple with its entablature, to a T. (The temple metaphor will work for this essay, though my life could just as easily be described as a puddle of rain water, or the melted end of a candle stick; those images are much harder to paint, however, and only deviate from the point; what I mean to say is, I moved to New York to study at my university, and everything outside of that purview is in support my studies, or who I was fundamentally before moving here.)

My life in school is divided into three parts: Study, Reflection, Meditation — my superstructure. My life outside of school consists of Teaching, Exploring NYC, Writing — my substructure. Meditation and writing are interlocked, and therefore act as one main point of intersection for my two “lives.”

The “Study, Reflection, Meditation,” concept I borrowed from an essay I read last night before bed titled, “The Wisdom of Silence,” by Khenpo Wangdak. In his essay, Wangdak divides the spiritual life into three practices, indispensable on one’s journey from sound to silence.

“Thopa is the Tibetan word for hearing. When you study, you listen to your teacher, read books, get ideas from friends, watch TV. Yet all of these are noise. Even when you read books silently you are mentally talking. Through listening or hearing, you get ideas or concepts.

“Sampa means to reflect on, sorting out as if through a strainer what to throw out and what to keep. When you start to look very carefully, then you know what to place in the trash.

“Gompa, the third and final phase, means to meditate, to get rid of the thoughts and quiet the noise.”

I am likening my “in-school life” to my “inner-life,” so the comparison with the spiritual is not far-fetched, at least for me. Yesterday, when I read the Wangdak essay, I began to, yes, reflect on my life as a student. And because I went to sleep after I finished reading, you could say I then meditated. Now I’m writing about it, afresh, building my “outer-life,” the publishing of these personal essays.

At workshop every Tuesday, two classmates present short stories to class. We read, and return the following week with critiques: that means listening to their stories on our own time, reflecting on the pieces’ strengths and weaknesses, and then putting them out of sight until class, when the time comes to speak and share our thoughts. This last step before returning to workshop is the third step, the meditation. Same with seminar: we are assigned readings — The Metamorphosis by Kafka, for example — we “listen” to the story, reflect on its imagery, read some extra criticism if we please, then put the story in our backpack (away, hush, until it’s time for class). Same with my translation seminar. Read, reflect, relax.

The “meditation” step is essential for another reason. It allows me to approach other work (the writing of my own stories) without distractions. Once a month it’s my turn to submit a short story. If I spent all my time reading books or listening to lectures, I would never write. If I had seminar reading swirling in my head or classmate’s ideas clamoring for reflection, then I would never write. When I want to write I have to light an incense, shock my senses; light a candle, pour tea, surround myself with the elements; turn off, and tune in; trust my mind to shut up, and let the flow of words stream or billow. And I don’t think I’m alone in this. Some writers hit the mat (yoga) before they write, as a means to quiet the mind. Others hit the flask before they punch the keyboard, as a means to shut the chatter up.

It’s spiritual. In those moments when I must toss out a pair of socks because of a tear, or when the floor boards of my apartment creak, or when all I have to eat for breakfast are two spoonfuls of plain white yogurt, I fall back on my driving metaphor for being in New York: being the monk. Hah. Seriously. Cervantes wrote of a father who gave his three sons three options for career paths: “Iglesia, Mar, or Casa Real.” Basically: “Cathedral, Sea, or Monarchy,” as in, the three careers open to men are to work for the church, or as a businessmen, or for the king. I view my university as a cathedral. I see myself as a man of letters, like the monks of the middle ages. Why not? I read dead men and women’s ideas, I transcribe them, I share them, and I write my own commentary, and my own stories in between. I lead a simple, not to say monastic, life. And I am learning to trust in a creative higher power. There is no other way, not for me.

Needless to say, there are silences between my teaching life and my school life. I teach classes in the mornings, and take classes in the evenings. I nap in between, during the day; naturally, I sleep at night, between taking class and teaching class. But more than that, these two lives are separated by a change of clothes, by different states of mind, by city transit and exploration (soon to come, reflections on El Perseguidor, by Cortázar, who calls le french métro a great watch, with each stop being a different minute on that watch). Being a teacher is the very opposite of being a student, by definition. And yet by being the one, I am better at being the other (at the metaphoric point where they meet, the Ts).

Let me end by giving three specific examples of intersection between in-school and out-school life: One, this week was the first week of a new 8-week session at the language school I teach. We did icebreakers one day, and one of the questions I asked my students was: “If you woke up one day as an animal, what animal would you be?” — inspired by the Kafka reading. Two, one of my students from China presented his cultural mid-autumn treat, the mooncake. He brought some to class, and I had a chance to try it: spongy, sweet, and packed with five different kinds of nuts. It was delicious. This experience made its way into a short story I wrote, which will be discussed on Tuesday (the day this essay is published). Three, my university held a 50 year anniversary celebration of Gabo’s 100 Years of Solitude; I attended this in-school event on my out-of-school time; and it is only one among many events held at the university, a space for crossing, for meeting, for exploring.

My spiritual-scholastic-monastic-whatever life is supported by the outside-teaching-writing-practical life, returning to the intersection of a temple’s columns and entablature idea. Distinct, yet interacting. Together they form the architecture of my life in New York. Would you like to come in? Welcome. We’re performing a sacrifice today.