Writer of many home-study courses for Time-Life Educational systems, Ron Bradley, was the English learning trainer who helped certify me to teach others. He has this to say about reflection:

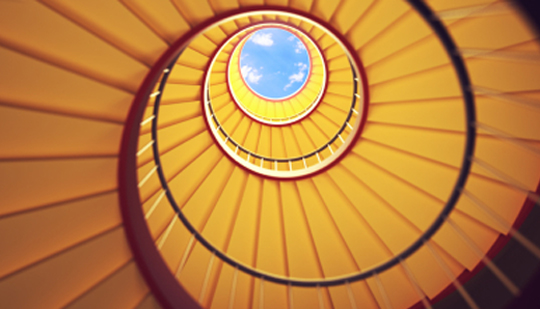

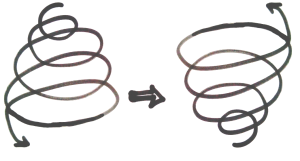

“[Use] reflective practice to improve your teaching and professional growth: ‘If you always do what you’ve always done, you’ll always get what you’ve always got.’ When we learn any new skill we improve that skill by thinking about what worked and didn’t work. Each time we try to do the skill, we think about how we can improve it. The Experiential Learning Cycle [detailed below] spirals upward and gathers more and more knowledge and skills. It builds on previous learning and uses reflective practice to move up the cycle. Just ruminating about mistakes keeps us going around in circles digging ourselves ever deeper.”

The practice is simple.

It can be used for any situation, affair, or even creative writing story, but for right now, let’s imagine you’ve just taught your first class at a new school. Your immediate feelings are: “Nervous, shaky, accelerated.”

You remember all the little mistakes you made, the laptop not working, the name of the student whose name you called out wrong. You cringe at having had too many students inside your small classroom, the building’s heater that cooked everyone over-easy. Oh, and you ran out of time before completing the objective.

This is called ruminating, not reflecting, and it does little to help you become a better teacher, let alone improve tomorrow’s lesson, much less the students’ learning.

What Ron Bradley suggests, based on the ECRIF learning framework, is to organize your thoughts on paper, and reflect on action.

Your initial feelings might mislead you. You deduce: “Ok, the whole day went wrong, and it all began with poor instructions. I have no idea how to give instructions.”

Before we analyze this fatalism, let’s take a look at what Ron suggests.

1. First, write Description. Write about what happened in the past tense. The key here is not to jump to analysis, and to remain objective. Keeping to one tense helps.

Not: “The whole day went wrong” (vague speculation), or “I have no idea how to give instruction” (unfounded analysis). But instead, choose one specific event, and write a concrete description. For example: “I gave instructions to the listening exercise verbally. The students in the front row nodded their head, but a few in the back, like Jitsuda and Asyera, only stared back at me. When I asked if they ‘understood’ they shook their head. I repeated the instructions, but slower this time. When I asked them if they understood the second time, they nodded their heads. I hit play. The laptop crashed. Two minutes passed before the laptop ran again. After getting it to work, and after playing the audio, I asked the students to pair up. A handful were left without partners, while others exchanged information with multiple partners. I asked Jitsuda and Asyera to partner up when I noticed they were alone, but when I looked down at their worksheets, they had nothing written. I stopped the whole class and ran through the instructions again, and played the audio again. The hour ended before we could review the answers as a class and assess their learning as had been the plan.”

2. Second, Analysis. After carefully writing objective sentences, and not analyzing what a student felt or not guessing why you did what you did in those objective sentences, now you can look back and take step two. Analysis: “I must have spoken too fast and used complex grammar the first time I gave instructions. Speaking slower helped a little, but I should have also tried using simpler words for this intermediate class, or modeled the exercise to help the students succeed. Also, I didn’t monitor students while the audio played, which would have let me know how many of them were listening with intent, and how many looked frustrated. I think the students who didn’t attempt the assignment, like Jitsuda and Asyera, must have not understood the instructions at all.”

3. Third, Generalizations. This is the silver bullet that will bring down many a negative and useless afterthought. After describing a scene, and providing analysis that is based on your concrete experience of it, now you must write generalizations, or truisms, that you have internalized, and that you can call upon to help lift you from your downward spiral. Here you use the present tense. For example: “Giving oral instructions rarely works on its own, especially when fast and complex. Slowing down can help. But following with ‘Do you understand?’ or ‘Does this make sense?’ doesn’t tell me if the students have actually understood the instructions. A better option is to model the assignment before, and to check their understand with a question like “Are you going to write your partner’s information on your sheet?” Of course, the best way to stay present with each student is to monitor during the activity. Immediate monitoring is a must.”

4. Last, write a Plan for Action. Once you’ve written what happened, an analysis of it, and you’ve reminded yourself of effective teaching practices, the only step left is to write what you will do next time (in the future tense, naturally). To quote Ron, “Not ‘I hope,’ not ‘I will try,’ but ‘I will.'” For example: “I will use simpler language when giving instructions for tomorrow’s listening exercise, and gesture “Don’t copy your partner’s answers” by covering my eyes. I will play the audio as many times as the students need to complete the assignment: first for general understanding, second for the fill-in-the-blank activity. I will ask 2-3 effective comprehension questions, such as “Are you going to copy your partner’s paper?” or “Can you guess what this audio is about?” I will pair the students, not leave them on their own to scramble for a nearby classmate. Finally, I will monitor right away to be sure each student is on task during the audio, and to assess how well each pair/student uses the target language.”

Notice how this method of organizing your thoughts can be applied to your creative writing. How many times have we heard “Show, don’t tell,” or “What is at stake for this character?” or “What does this character believe?” maybe even “What’s the point?”

Writing intently, giving concrete description, sprinkling analysis that follows from the text (not adding authorial conjecture), and giving your characters a chance to state what they believe or what they will do next time, are effective methods of story telling.

Notice the Experiential Learning Cycle in this next example:

Kathrine was a three-legged cat. She loved to go to the park. It had been a while since she went to one. “Parks are the best,” she said. “Tomorrow, I will go to the park.”

Ok, this is a silly example. But notice how the first sentence doesn’t involve any analysis (not that she’s a sad kitty, a lonely kitty, a hurt kitty; these are assumptions one could make about a three-legged cat, sure, but not concrete description). Since the first sentence doesn’t state any analysis, it allows the reader to form her opinions. Once the reader is grounded in concrete reality and her own opinion, now the next sentence can add an internal dimension to the story, analysis. We aren’t shown that Kathrine love the park, only told that she does. Were we inclined to continue the description in-action, we could have written “She gazed at the frayed edges of a post card depicting Washington Square Park, and imagined herself there.” That might have alluded to her love of parks, even alluded to her putting off a park visit (“frayed edges”). The following sentence: is it description or analysis? One might assume because time is given, it’s objective description. But the fact that we’ve written “been a while since” gives it airs of analysis. No concrete specific time is given, so this sentence is analysis. Note the difference in this descriptive sentence: “It had been three years, four months, two weeks and five days, since Katherine’s last visit to the park.” With it we were able to provide precise temporarily, while still hinting at Kathrine’s feelings, without dictating as an author with a simple “It had been a while since.”

The next to sentences are “Generalization,” and “Plan of action,” and they follow the Experiential learning cycle. As you’ll have gathered, modern prose seems to prefer strict “description”-based writing (“Show, don’t tell.”). But an agile write will recognize, and utilize all four modes of writing.

Can you write a four to six sentence story, using all four of the Experiential Learning Cycle modes? Write it in the comments below.

Even better, do you have a moment in your life that spirals you downward? Try writing concrete description (difficult, but not impossible), and only then adding your analysis to it. Add your generalizations and truisms about life as a third step, to guide you toward a fourth and final step out of your depression.