Today we looked at what readers explicitly crave for: characters. Although not superior to plot, according to Mr Bell, and even to Mr Aristotle, characters in the modern age mean a lot to readers. I suppose this comes from how we need stories in order to live our own lives. Yet it is in imitating our role models that we apply those lessons, like guides to a map.

In other words, while a plot may drive the play’s lesson (what stays in our mind long after the story ends) how we internalize that lesson, that is how we believe it to be true, is by seeing that lesson enter the lead character.

As Mr Bell puts it, citing A Christmas Carol, we believe in the power of human good not necessarily because the order of events. But because we see how miserly Scrooge was in the beginning, compared to how kind he becomes at the end.

This dramatic change in a character needn’t occur to such a wild degree, in that direction, nor serve as the story’s central moral. The Scrooge story, for example, is a story about change, specifically of the interior. You may also claim that Cinderella is a story of change, but of the exterior. These changes also occur in subordinate to larger necessity, not always as ends in and of themselves. Take Luke Skywalker, who goes from nobody to Jedi knight, an important stepping stone. But this isn’t the most important change, nor moment in Star Wars Episode 4. Destroying the Death Star is more important, because it is the ultimate purpose of the lead’s transformation. (At least in that episode.)

What I am seeing then is that a character change does the plot good, and can be good in many ways. As the main point of a story, or as part of the main point, or even a perfect blend.

One example that hit home was the one about Dorthy in The Wizard of Oz. She begins the story a dreamer, someone who wishes to live somewhere over the rainbow. Anywhere but in Kansas, that is. But what is she clicking her heels to at the end? The line, “There’s no place like home,” becomes her mantra of maturity — realizing the value of where you are from. In a word, she becomes a realist.

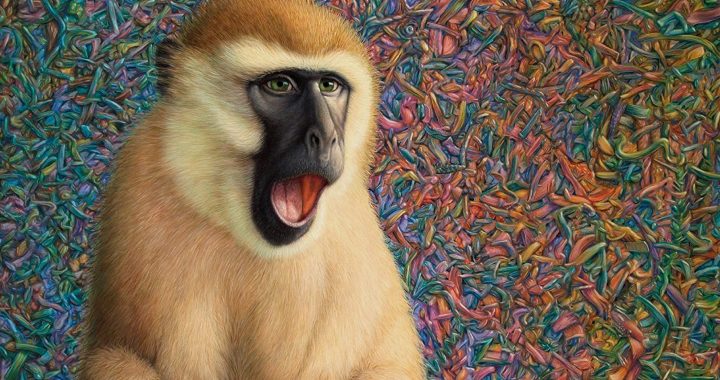

Nothing like a wild adventure to teach you that. Even in a story that aims to address a lot of stuff (flying monkeys, the gold standard . . .). Anyway, like I said, the story hit home for me!

. . .

Hopefully, why we writing characters who change is clear. It can either be an important focus, such as with Dorthy. Or a minor focus, like with Skywalker. It can be ultimate and interior as with Scrooge. Or ultimate and exterior as with Cinderella. Actually, what is more curious is how we change, how we write these changes.

Mr Bell puts it like this. We have layers, with the deepest layer being own on Self-Image. Think mirror in Snow White, who sometimes tells you what you don’t want to know. Next comes our Core Beliefs, followed by Values, then Dominant Attitudes. Then at the very outer layer are our Opinions. All are layers to our identity.

The closer to the surface, obviously, the easier to change the layer, without affecting the core. Yet if you change enough of the outside, then eventually the inside will shift. This happens in many stories, during the course of its telling. Think any Pygmalion tale. Legally Blonde, Mean Girls, Princess Diaries. Theses women experience superficial changes that, combined with gradual shifts in attitude and values, produce a development of Self-Image.

The opposite case would be for a radical shift to occur at the start of a story. Some deep, penetrating change that affects the character’s Self-Image, causing the other layers to collapse. It seems like a lot of stories begin by changing this Self-Image, and then play out the reconstruction of a new identity throughout the rest of the story. I’m thinking Jack Black in School of Rock, who must restart his life once his whole Self-Image as a forever-young rocker is destroyed with one bad crowd dive at minute 3 of the movie. Or any super hero movie, in fact, where your very, very core identity changes after a freak chemical accident. And you must explore your new self, develop new opinions, and save the day the rest of the story.

As a final example of character change, it occurs to me that there are also stories where a character deliberately doesn’t change, despite external forces, pressure, or changed circumstances. In Parasite we see a raggedy family elevated to riches, although they hardly know how to live the rich life. And die off quite as classless as they began. Also, any Prince and Pauper story, or Freaky Friday story (where the characters don’t necessarily change at the end, but become more appreciative of their own value in society, plus their opposite’s value). I’m sure we can think of other stories where the characters do not change at all. Odysseus or Samurai Jack or even Carrie Bradshaw. The joy of watching these heroes and heroines comes precisely from their ability to resist external pressure, stay true to themselves, and kick butt! No change here.

. . .

Now for the exercise. Mr Bell asks us to: Analyze a favorite novel or story that has a big change happen to the Lead. Underline all the passages where the lead is being challenged. And put a checkmark in those passages that show the challenges have affected the character.

I would like to quickly analyze Konstantin Levin from Anna Karenina. First of all he is a great example of interior change. Second, because this change rises slowly, over a thousand pages, until it all floods him at the very end, I am lead to believe that this is the point of the whole story. Lastly, something about his change specifically helps me remember the order of events (plot), especially in contrast to the change within the lead character herself, who seems to mirror Levin’s change, but in reverse, for the worst. Two perpendicular lines of change, within two major characters, over a 1000 pages? Change here, my friends, is critical to the story.

We meet Levin as a “strongly built, broad-shouldered man with a curly beard,” quite literally bursting onto the stage during a civil conversation between Oblonsky and some other classy Muscovites. Levin is impertinent, but shy, and at the same time angry, as he speaks. He stammers, too. And blushes, not like men do but like boys do, and hates to be compared to his successful half-brother. Never have I felt more attracted to a character by his introduction!

In a word, Levin is a ball of contradictions. His first real challenge (or battle of his opposing interior forces), comes to head a few chapters later. Despite being shy and awkward, Levin takes a massive step forward when he proposes to Kitty for the first time. In the comfort of her home, she sees him as “shy” but with “shining eyes” and “powerful figure.” He stammers the words, but gets out a sort of proposal. And yet Kitty, herself conflicted, must refuse him. Levin in turn avoids eye contact, feels the need to run away, and the first real pain of being internally inconsistent. I would even call this his first alea iacta est, the point of no return moment, the “first door” as Mr Bell puts it. After which, Levin’s outer Opinion begins to align with his Dominant Attitudes.

Later in the story, after Levin gives up on Kitty and returns to his farm, we have the famous Chapter 5, Part III passage of him mowing the grass. It seems mother nature erases all Opinions and maybe even Dominant Attitudes in Levin. In his “moment of unconsciousness.” The longer he mows the more often “the scythe mowed of itself, with its own consciousness . . . and as though by magic the work turned out regular and finished by itself.” It’s the first time we see Levin so chill and at peace.

It’s as if hard work and manual labor washes the otherwise awkward and nervous man. Maybe he doesn’t need so many Opinions of himself in order to do good. Of course he will be swept up by politics and village council meetings, where he must put his Core Beliefs on paper. But all the while, he will feel a renewed vigor in his studies, as he further aligns his insides, every time he works on his farm.

Halfway through the story, Levin conquers his fear and proposes a second time to Kitty. This is a wonderful turning point for Levin. Not only does he see Kitty also had feelings for him, but he seems to have aligned his Value of Family, with the Core Belief that Kitty is his soulmate. (My words, not his.) The two lovers arrange to get married briskly, which is fun. Meanwhile, Levin starts to realize that “he and his happiness constituted the chief and sole aim of all existence, that he need not now think or care about anything, that everything was done and would be done for him by others.” It’s as if having his Core Belief’s validated by Kitty’s affirmation meant he shouldn’t combat other’s opinions about trivial matters. He’s developing a new Dominant Attitude. Perhaps his dodgy, dopey Self-Image might change. But not yet.

“Passing through the dining room, a room not very large, with dark, paneled walls . . . Levin walked over the soft carpet to the half-dark study, lighted up by a single lamp with a big dark shade. Another lamp with a reflector was hanging on the wall, lighting up a big full-length portrait of a woman, which Levin could not help looking at. It was the portrait of Anna, painted in Italy by Mihailov . . .

“Levin gazed at the portrait, which stood out from the frame in the brilliant light thrown on it, and he could not tear himself away from it. He positively forgot where he was, and not even hearing what was said, he could not take his eyes off the marvelous portrait. It was not a picture, but a living, charming woman, with black curling hair, with bare arms and shoulders, with a pensive smile on the lips, covered with soft down; triumphantly and softly she looked at him with eyes that baffled him. She was not living only because she was more beautiful than a living woman can be.”

Who could forget this passage near the final stretch of the novel? I think it is so genius (yes that word!) of Tolstoy to include a portrait of Anna in a book about her. Taking a pause from Levin, I would like to remind the reader that the main character of this book Madame Karenina. That as we read we are supposed to follow her; everyone else a pillar or a mirror of her. We are supposed to condemn, pardon, or defend the woman — it would be impossible to ignore her. Certainly based on her actions, but also based on the actions of others on her, not least of all society at large.

So it’s quite interesting, returning to our hero Levin, to see his reaction to Karenina at this crossroads. After seeing her Self-Image, captured beautifully, he immediately encounters the actual woman. Whom he will call “a true woman” after interacting with her for a bit. He is clearly smitten by her, but not to the point of exaggeration. Closer to reality, he is attracted because “. . . besides wit, grace, and beauty, she had truth.” She finds Levin funny, she makes him laugh too. They both share real thoughts from their Core Beliefs. And it’s almost as if they could have been the real siblings, not Oblonsky and Karenina. But, if that had been the case, one would have saved the other long before.

They part ways, after barely sharing the stage for ten, fifteen pages. Yet in this brief falling-star moment, Levin changes deeply. Becoming ready for his final epiphany.

In Part XIII, after the fall of the Madame, with Kitty and the kids playing back at the house, Levin goes off to wander the woods a little bit. There are creeks, it seems like a beautiful day, but he is tormented. Aside from little errands he has to perform, he ponders existence itself to himself. “All that spring he was not himself, and went through fearful moments of horror. ‘Without knowing what I am and why I am here, life’s impossible; and that I can’t know, and so I can’t live,’ Levin said to himself . . . It was an agonizing error, but it was the sole logical result of ages of human thought in that direction.” So we see him finally stripped bear.

No Opinions he cares for. No Dominant Attitudes he upholds. Values are hard to define. And what are his Core Beliefs? Levin feels he cannot even talk about this anymore, if all he wants is truth, and truth seems torn in different directions. Orthodox church? Catholic church? Live for the belly? Live for the morrow?

At last, after speaking with some of his field hands and remembering the lessons of his childhood, Levin comes to the realization that there is more to life than what his mind can grant him. Something he just knows. As he lies on his back, gazing at a cloudless sky, Levin almost sees himself. A beautiful string of realizations, like light bulbs going off, brighten Levin. All worth reading. All sinful to copy-paste here! But worth mentioning is that after his self-discovery at the end (Life is good, I am good, Life is me, I am life) reality seems to hit him from the rear.

Mr Bell says it isn’t enough to give your characters epiphanies. But to put your characters to the test. Like Mr Scrooge tossing a poor boy a big gold coin at the end of A Christmas Carol. Readers want to see this change manifested.

So we see Levin, fully aware of himself, and seeing the difficulties of everyday life getting in the way of his true self. A wife gets sick. A kid disappears. The field hands rip him off. He must do someone a favor. These mundane realities pull Levin from his peaceful core. But perhaps he can imbue those moments with his goodness, his serenity. It’s ok to make the mistake of looking your cool or your zen. But we see Levin at the end weathering a storm with his wife out in the woods. Arguing with this brother. And loving everyone at dinner. A moment of communion and peace.

On the last page, Levin knows himself as good. He knows what to expect, too, that sometimes he’s bad. Also, knows what he must do in those cases, to correct himself. And that ultimately, it is within his power to continue being good, continue being himself. Despite the ups and downs, life is very much worth living.