(Note from the writer: I wrote this back in March, but never published it. Given the recent news of HBO dropping the film then picking it back up, I figured to give this piece some light.)

Folks up in flames over recent Oscars? “Frankly, my dear, I don’t give a damn.”

Last weekend, my grandfather shared this opinion piece from The New York Times. In it, the journalist rants against the meddling orange head of the executive branch. The president has done it again, he upset Twitter, the film world, and everyone in between. This time, however, it was over his remarks at a recent rally, dismissing the first non-English movie to win Best Picture, from South Korea, Parasite.

As it went, Trump decried the Academy for awarding a foreign film with its highest accolade, as opposed to Best Foreign Film, which it also won. How could this happen, he added, when trade with South Korean is as bad as it is? Truth be told, even I found the selection odd, but not because of economic policy. Rather, it was because I had no plans to see the movie before this week.

Unlike the president’s constituency, my reason didn’t stem from a disgust for people different than me. Actually it was my grandfather who first watched the movie, who dissuaded me. When I asked him how it was, curious to find out, he nearly spat as he told me how awful it was, how terrible the translation was, and all sorts of negative, disparaging details. In a way, he spoiled the movie, without giving away the ending.

Months later, when we talked about it again, discussing how the Academy gave it Best Picture, and about Trump’s fiery comment, I was anxious to hear him finally agree with the demagogue . . . yet, despite what I thought, I was stunned to discover that somewhere along the way my grandfather had changed his mind. Now he thought the movie was great. It was like learning a family member had flip-flopped midway during the war, the scallywag.

But, he explained: “if what I said made you not want to watch it, then what I say now will make you want to watch it; Parasite is the kind of movie you need to think about, he said, for a long time.” And that’s when he shared the article about Trump and how he deemed the Academy’s decision ridiculous.

Maybe the president should watch the film, and think about it, too. I finally watched it last night. Because, after so much debacle, why not form my own opinion? It’s an awesome film.

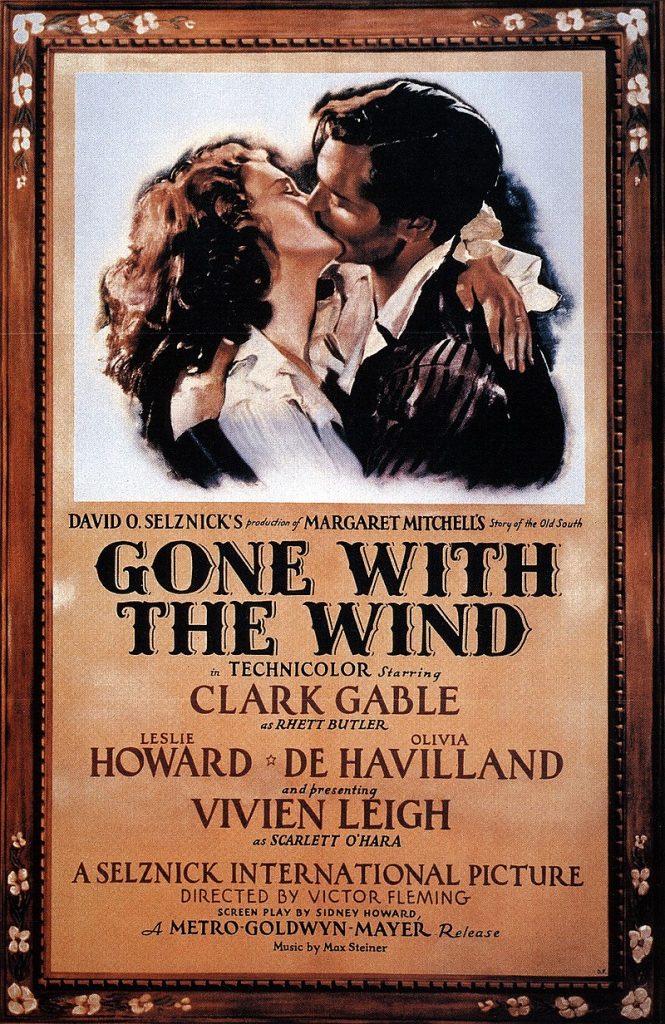

Fun fact: did you know that Clark Gable actually added the brusque, “Frankly,” to the character Rhett Butler’s famous last line?

So what do Parasite, Trump, and my grandfather all have to do with Gone With The Wind? Well, for starters, they all have to do with judging things second-hand, or avoiding them because of someone else’s opinion.

More relevant, however, is how I had just finished reading the final (one thousand and thirty fifth) page of the book, when we discussed the NYT article. In it, the journalist also rips on Trump for missing the good ole days of cinema, reading the crowd’s mind with a smirk when he pleas, “Can we get Gone With The Wind back?” rotating his hands in a backwards motion.

Were one inspired to be fair, the president could be understood as having meant he missed raw portrayals of American life — of which the 1939 adaptation does a brilliant job — plus, the Academy is based in America, and should bestow its highest honor to an American movie. (Never mind that its expressed mission is to “connect the world through the medium of motion pictures.” Emphasis mine.)

But, instead of being fair, at least to the art itself, the NYT, along with Twitter, along with the Left, merely quoted a soundbite, then compared the comment at the rallies to the story itself, going completely over board, as John Oliver did, when he call both: “excruciatingly long, incredibly racist, and centered around a rich creep who leaves a woman crying in a mansion.” Ignoring what the story actually says, they simply made a connection, hit print, then moved on.

True, Gone With The Wind shows the lives of Southern Aristocracy during the 1860s, but to dumb it down to nothing but a commercial sponsored by the Klan? You might as well write the following lines over your face with a Sharpie: “I didn’t read it, but let me comment.”

Frankly, it’s an annoying supposition, to judge the story as “incredibly racist” simply because you want to make a joke. It reminds me of the Simpson’s episode when Apu passes his citizenship test:

Let us be honest. The adaptation does depict what some might call a “politically incorrect” version of the Civil War and Reconstruction South, in which the audience is asked to empathize with slave owners. But to claim that the film’s sympathy lies with the plantation system, and not with the earth itself, is to hardly get the film.

The Academy did not commit a sin by giving it ten Oscars in 1939, including Best Picture; nor did it fall prey to some internal inconsistency by awarding 12 Years a Slave, the opposite take on the same South, the same Oscar. Both films are powerful narratives on the human condition. Is it fair to say there are different conditions for different humans? Wouldn’t it also be fair to admire art from all walks of life, on our journey to a more complete appreciation of all our lives?

Another fun fact: the adaptation of Gone With The Wind was released soon after the invasion of Poland by Nazi Germany. Whereas the Nazis had initially praised the book for depicting Americans as greedy, naive racists (*ironic*), they promptly banned the film for its international success, its call to rebellion, and its female protagonism.

While Europe was falling apart like a tower of poorly placed Jenga pieces, and the world was preparing to defend or destroy human civilization, it’s important to note that both the film and the novel are best understood as works about the folly of love and war, rather than about race — something other movies and novels treat much more explicitly, and purposefully.

Quick recap on theme: The spoiled, ruthless daughter of a wealthy plantation owner survives the Civil War and begins to rebuild her life. Unfortunately, she hardens in the process, thus alienating herself from those who love her the most. It isn’t until the mist of Reconstruction clears that she realizes her mistake, but perhaps by then it is too late, everything’s been swept away.

Gone With The Wind — for anyone who has thought about it for “a long time” — is more interested in how pride can lead you to war, how false love can seem real, or how useless it is to yearn for a bygone era; and less about white superiority. But don’t take my word for it, just try the following thought experiment:

Imagine you wanted to write a play based on the protagonist. If you took out slavery, couldn’t you stage an engaging, powerful plot between the main characters, although in some other setting, during some other war? On the contrary, if you removed the love conflict between Scarlett, Ashley, Melanie, and Rhett, but kept the war, kept the slavery, then what would you have? Something no one would pay a ticket to see.

Now, inspired by the brutal honesty of Captain Butler (a.k.a. that “rich creep,” who is not even the central character, thank you very much, Mr Oliver!) I intend on being honest myself, admitting why I spent the last dozen paragraphs prefacing this post, which was originally supposed to be a review of the 1936 novel . . .

In a bombshell, I didn’t want some stupid ass telling me only racists love this book, the same way Trump was called out for liking it.

To hate someone who hates everything is one thing. But to attack Gone With The Wind, thereby dissuading intelligent people from ever reading it?

Nah, liberals. We’ve got to defend art. Not trash it. Just forget the president for a moment: the fact that he wants to “go back to a simpler time, to a golden age of cinema,” or whatever, demonstrates, in the most epic way, that he missed the moral of the the story from start to finish. So, please ignore his remark. And pick up the book.

Whatever a work of art is supposed to do, Gone With The Wind does it brilliantly. It captures the human imagination. It depicts a pivotal moment in American History. And, most importantly, it a recounts a love story as devastating as the war that surrounds it, giving the reader the highest form of emotional catharsis, through the highest degree of narrative dexterity.

Not for nothing is it considered “a classic,” even an international classic, especially by my coworkers halfway around the world, who quoted the actual last line to me for four weeks, as I read. “Tomorrow is another day!”

Like all great stories, its reputation precedes it.

I don’t mean the obvious fact that a great story well-told will cause a ripple throughout later generations, who first hear about it and then discover the greatness for themselves.

I’m referring to the fact that when we learn about an older work of art, because of someone, even someone older, there is like a burst of light that shades our eventual encounter with the classic. (Please refer to the title of post, wherein my hope is to make you read the book; followed by my grandfather’s rave or rant of Parasite, which made me want to see it or not.)

This shading, or praise effect, reminds me of what a mentor once told me about the power of headlining acts. Headliners win the crowd before they even step out on stage, he said. Before the final show the lights go down, the audience hushes, and big flood lights dash against the curtain, with fireworks blasting, and sparklers roaring. That’s how you should make an entrance. But also, that’s how you win the crowd before ever showing up.

And that’s how Gone With The Wind entered, with interspersed praise throughout my life.

The first time I heard about it was in seventh grade, Texas History class. Some classmate had finished her assignment early, someone who usually did, and used to hand in completed work directly to the teacher, then whisper about whatever. This one time, though, it was about a strange movie she had seen with her mother.

“Why is Scarlett smiling the morning after Rhett comes home drunk and he carries her off into the bedroom?” she asked, guilt on her face as she talked a taboo subject with the teacher, meanwhile everyone else was copying answers from their neighbor. “I thought — I thought Scarlett didn’t love Rhett?”

I don’t remember if the teacher dropped “the r-word” in class, or not, but I do remember him alluding to how some viewers considered this a textbook case of marital rape. “But,” he replied, “on the surface it’s confusing. The fact that we see Scarlett’s cheeks crimson with happiness, and smiling, means it’s for a good reason.”

“So . . .” asked the classmate, in an unbearable whisper that made the creaking of my chair all the more squeaky, as I leaned in closer to hear the answer to the question, “. . . what’s the reason?”

“The reason?” the teacher said, with a snort and a chuckle. “You’ll have to read the book.”

If you watched it, read it. If you didn’t watch it, first read it. And if you already read it, you know you’ll want to read it again.

According to the jacket cover, Margret Mitchell began writing in 1926, and finished in 1936. This is worth considering, if only for two reasons. One, while America transitioned from its roaring decade to its Great Depression, to isolationism, the story of Scarlett O’Hara follows a similar trajectory. Two, while the major literary trend to survive those ten years was modernism, this book is neither experimental nor minimalist AT ALL. What I mean is, perhaps its massive popularity stems from these two factors: a rejection of trends, and its reflection on the national milieu.

It’s international appeal, however, could be because its treatment of universal themes, riveting attention to detail, and page turning plot. At least that’s how my mother-in-law put it. It’s her favorite book of all time, and she was the one to give a copy to Ela, who read it twice in high school, making it her favorite book too. Last Christmas, Ela gifted me a copy, making me enjoy it too.

As suggested by this chain of recommendations, it’s better to read the book first. It’s one of those examples of “the book is better,” seriously. Because when I read the book, I was so draw in, so engaged, so mind blown, and yet, I felt myself numb to the highs and lows of the plot, because none came as a surprise. If I had not seen the movie, then the last 100 pages would have been the absolute most craziest plot twists I had ever read. Unfortunately, I didn’t get that pleasure, and I had to breeze through the rotten crumbling finale just to end the suffering therein.

Yet, because I did watch the film first, I talked a lot about it half a post up, because most likely you watched it too — and now the best reason to read the book, is probably to get back something you were missing. Closure.

On the one hand, the film presents the main themes of the story, as if on a silver platter — impeccably served with a glass of brandy. But on the other hand, it creates some unanswered questions (as my grade school teacher meant) by not being thorough enough. However, if you read the book, you know the author Mitchell gives you e-v-e-r-y-t-h-i-n-g.

This book is a middle finger to “show don’t tell” theory, and a high-five to what a philosophy professor once told me: “There are two way to hide the truth. Either say nothing, or say so much no one can find the truth.” This book says it all, and with such passion, it feels like you’re in a log cabin, listening to your granny tell you a story about moving on with your life, in the feisty soprano of a woman who has learned this lesson first hand (and ok fine maybe shes a little racist!)

Final analysis.

I mentioned earlier how the book 1) captures the imagination, 2) depicts a pivotal moment in American history, and 3) tells of the folly of love and war.

First, the attention to detail makes you see things as if for the first time. The sentences are flowing and uninhibited. And the things the characters do or say makes you chill with envy, regret, pride, or glory.

Second, this book reveals the hearts and minds of interconnected members of a similar cross-section of American society, as they journey from the highest strata of society to the bottom. If the term “Great American Novel” refers to a canonical work of literature that is thought to have captured the spirit of American life, then this book earns the GAN stamp like a war hero gets the Medal of Honor.

Third and last, the main idea of the book is folly. View it as you wish, but to me this thick book goes deeper than the skin of things. In fact, my dear, the great mistake is to do just that: to stay on the surface of things, to be naive.

Tada, let’s close. Here’s a parody of the whole story. Just for kicks.