“I would like to be able to look Maitreyi in the eyes…” — Bengal Nights, 1933

For a powerful narrative set in postcolonial India, told by two powerful minds, one pair stands to be compared and contrasted. These are Mircea Eliade’s 1933 Bengal Nights and Maitreyi Devi’s 1974 It Does Not Die. Together, they recount two compelling yet competing versions of the same passionate love story that never saw its happy ending. At once blurring the boundary between memoir and poetry, the sacred and profane, traversing continents and decades to do it, in the end, both break your heart.

Here they are — the University of Chicago Press editions — a semi-autobiographical novel in orange and a memoir full of poems in violet:

An abstract. In 1930 India, a young Romanian scholar begins an affair with a Bengali teenager, the daughter of his host and mentor. As tensions mount between colonists and colonized, the heat of an inevitable independence movement rising, both lovers are forced to abandon their love right as their relation reaches its apex, leaving devastated lives in their wake.

A real story, with juicy roots and sour consequences. Imagine mixing romance, philosophy, and geopolitical forces beyond anyone’s control, to tell a boy-meets-girl’s worst nightmare, just as the many waters of the Ganges-Brahmaputra delta merge and flow from the Himalayan Mountains. And you get these books.

“If I hesitate in beginning, it is because I still have not managed to remember the exact date of my first meeting with Maitreyi.” — Bengal Nights

Eliade’s side of the story was written only a few years after the real events transpired. Bengal Nights is presented as a novel, narrated from the point of view of a Frenchmen named Alain. In sketching the differences between both texts, it would pay to examine three key points where Eliade’s fiction departs from reality.

First, the narrator is French, not Romanian. This change magnifies the colonialist element of the drama — because a foreigner from a world power in bed with a local from the most revolutionary part of the country only highlights the reality of the Indian movement — where a father must force the European seducing his daughter to leave his house. Eliade could have written himself as an Englishman, but the parallel might have been too on the nose, and off key. At its heart his novel is a love story, so it makes sense we read about a youth from France, with all its romantic allure and philosophical undertones.

” ‘ I love you, Maitreyi, I love you…’

” ‘Say that again, in your own language.’

“A stream of French — whatever came into my head — came pouring out.”

— Bengal Nights

Second, and this is the deviant point that prompted Devi to pen a response, is that Eliade wrote in sex. Although how both authors describe their bare skin touching could make whiskey hard, Devi states in the first half of her book outright that theirs was a sexless relation. She would have been 15 going on 16, and Eliade 23 going on 24. Even in a country that betrothed its 12 year olds to middle-aged men, examples of which are given in both texts, still, those marriages are sanctioned and engineered to produce the correct caste offspring.

Devi, I believe, at the end of the day, would never have gone against her spiritual duty to marry an Indian. So on the surface, after losing ourselves to the drama painted by Eliade, we are sobered by her denial that it ever happened. Not to mention a 15 year old Bengali entering the bedchamber of a European nine years her elder smells of a writer’s imagination. We move on.

“Later, I wondered if there were not ways of making love other than those we know. Finer, less obvious ways: the secret conquest of a woman by a caress or a witticism — or by intelligence, by which weapon she would belong to the beloved more totally than in the most perfect, most ecstatic, of sexual unions.” — Bengal Nights

Third, the sister of the Devi character in Bengal Nights suffers from a terminal mental illness and passes away, but not before tattle-telling on the hapless couple to the parents. It is the sister’s fault they were discovered. That Eliade has the sister character go insane and die allows for a cathartic literary revenge, not only for the author but for the reader who deplores such a snitch. Unlike in real life, where there was no death, just gossip and heartache at the tearing apart of two youths, the sister doesn’t actually die.

Note here that, as much in the fictitious account and as in reality, the cause of the separation is the same. No exaggerated walk-in of an acquaintance during coitus, or invented Fray Lawrence character, only a younger sister, seeing the two share a romantic kiss by a lake. A family member causing their breakup isn’t just real life, Eliade might have realized, but a literary element: the family, that is the primary social force of Indian society, broke the couple. Just one instance where fact and fiction compound.

“How incabable we are of capturing the substance of vivid joy or pain at the moment of its experience.” — Bengal Nights

Devi’s novel addresses the discrepancies written by her former beau as impetus to author her work, It Does Not Die. Her medium, calling for truth, is the memoir; she recounts the forbidden relationship of 1930. But her style departs in a drastic way from Eliade’s straight-forward prose. Devi instead utilizes a blend of verse and erratic prose, peppered with at times simple storytelling, to orbit around various feelings that seem to arise and disappear as the author recalls and records her side of the coin. Notice the style: so flowing, yet jabbing, elusive, yet sustained.

“It’s on a moon-bathed night or on an evening quivering with the trembling light of the glow-worm, we move away together from the crowd, [my sister] will not leave us. She will run to catch up. I say to myself, Such Distance can come between two, even when walking side by side! But I have never discussed all this with him–not even how much I love him, because I am not sure of myself, I do not know whether this constant longing to see him, to be near him is really love–who can assure me on that point? Moreover, he will then become complacent–the bird of jealousy will fly away–I don’t want that–I like it more than anything else.” — It Does Not Die, 1974

If this were a high school paper, then I might have been tempted to quote more from both texts, thereby churning out an extraordinarily long post. But I’ll stick to analyzing one critical moment, a single conversation roughly at the start of both books, that struck Eliade enough to write it, provoked Devi enough to rewrite it.

According to Eliade, this conversation arises when discussing the nature of guests being sent by God:

I had stressed these last words. She looked at me, reflected, closed her eyes, and when she opened them they were full of tenderness and affection; I had not seen such an expression in them before.

“I am wrong, no?” [she said.]

“How can I say? I am not a philosopher.”

“I am a philosopher,” she said at once, looking at me intently. “I like to dream, to think and to write poetry.”

“And so that is philosophy, I thought, and I smiled.”

And then Maitreyi changes the subject and speaks to Mircea about Tagore and her mother. What’s funny is that after his stay in India, Mircea earned his PhD in Yogic studies six years later, and devoted the rest of his life to philosophical inquiry, claiming to have always remained psychically connected to the young woman who had inspired the rest of his life.

According to Devi, however, the conversation instead arises when recalling a poem she wrote that her father half praised:

Mircea smiled and said banteringly, “How can a little girl like you write philosophical poems.”

“I am not a little girl, and I am a philosopher — a seer.”

“Yes?” He raised his eye brows, obviously amused.

“Of course, one who sees, or aspires to see reality, is a seer, and I am longing to see.”

And then Mircea asks Maitreyi to read him her poem, she following him into his bedroom. Notice how she doesn’t expound on the definition of Mircea’s future career (so it wasn’t her? only himself?), rather calls herself the less academic, more mystical, yet ironically more realistic sense-centered “seer.”

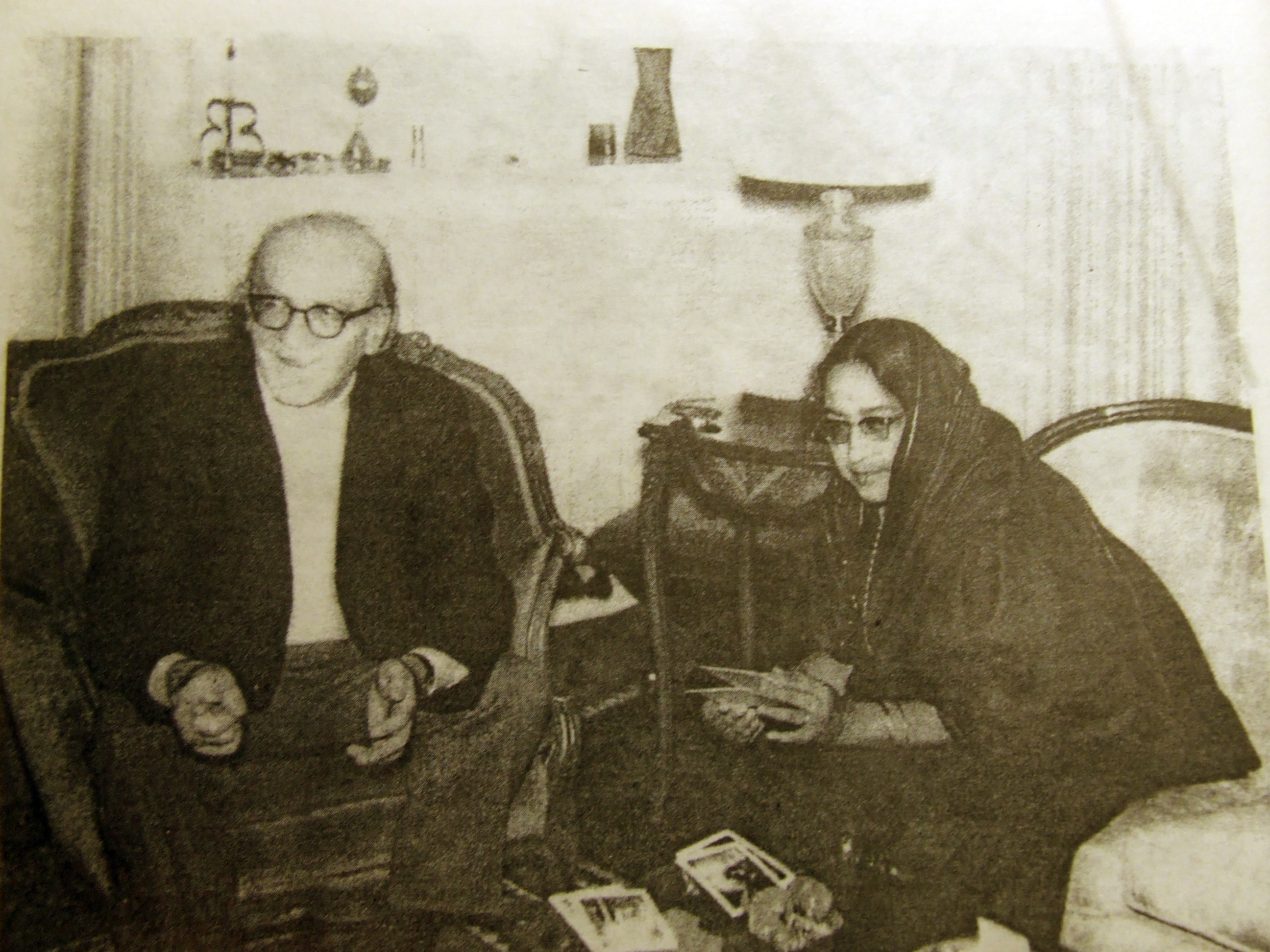

Maitreyi is seeing back, seeing into the future. She goes to his university office in Chicago forty years later and sees her long lost love, fulfilling nothing less than the last wish in his book, stating, “I would like to be able to look Maitreyi in the eyes…” She recounts that he wasn’t able to so much as look her in the face.

“By remembering Mircea I have not given anything to anyone else–it is only I who have gained a third eye to see the world.” — It Does Not Die.

For a moment the Adam and Eve story comes to mind, something Eliade would have studied intensely. Adam came first, then Eve came of him. There’s this myth that Man looks unto nature, being of nature, while Woman looks unto Man, being of Man. Eliade wrote about the events of their joint past, in a leveled literary form; while Devi took the liberty to express her very wild or high-minded voice revolving around this single man.

I don’t know, it just stikes me. Not saying Devi isn’t a deserving writer in her own right, the winner of some of the most important literary awards from her country, and a protégée of a great Indian philosopher whose name was . . . there I go again, linking her to someone else. In any case, take it as a fact, her book came second and was a response. Her thesis is Eliade. Her mission: to return to him, if only to grant his final wish.

“That great [phoenix], built with the illusion of hope, whispered to me, as we moved towards an unknown continent, crossing Lake Michigan, ‘Do not be disheartened, Amrita, you will put light in his eyes.’

” ‘When?’ I asked eagerly.

” ‘When you meet him in the Milky Way–that day is not very far now,’ it replied.”

— It Does Not Die